I Dig Sports

Ronaldo: I would be worth €300m in today's market

Published in

Soccer

Wednesday, 21 August 2019 04:38

Cristiano Ronaldo has said transfer fees in football have got out of hand and that a player of his calibre in the market would now sell for €300 million.

His transfer to Real Madrid from Manchester United in the summer of 2009 was a then world record £80m, but eight years later, Neymar left Barcelona for Paris Saint-Germain for €222m.

- ESPN fantasy: Sign up now!

- When does the transfer window close?

Asked what he would likely be sold for now, he told Portuguese TVI: "Based on how football is nowadays? It's difficult to calculate.

"Today there is a lot of emphasis placed on potential and the football industry is different. I'm going to put aside [Portugal international Joao] Felix's [€120m transfer to Atletico Madrid from Benfica] case. Nowadays, any player is worth €100m having proved nothing, there is more money in football.

"A goalkeeper, a centre-back is worth €70m, €80m -- I don't agree. But this is the world which we live in, the market is like that and you have to respect it. Is there a football player that has more records than me? I don't think there is a player that has more records than me."

Ronaldo left Real Madrid to join Juventus for €100m last summer and, pressed on what his worth would now be, he added: "If I were 25, if a goalkeeper is worth €75m, a player that does and has done what I have done in recent years has to have a value of three or four times that, easily, but I no longer have that desire."

The 34-year-old also said "the challenge" of winning individual and collective trophies at the top level keeps him motivated to continue playing football. The Juve forward said he could retire next year if he wanted as he has amassed a fortune in wages, endorsements and investments yet the temptation is there to play until he's 41 as he craves more silverware.

"My motivation is my obsession for success, I admit it," he said. "But it is a good obsession.

"I know I'm already in the history of football. I know that I'm one of the best in my field but that is not by chance. I could end my career next year but I could also play until I'm 40 or 41.

"It's about the challenge. I still feel motivated to win individual and collective trophies, and if I wasn't, I would end it [career]. I have everything I want, I have an excellent family, I have spectacular businesses. From a financial standpoint, I'm very well. I don't need football to live well. I will live well all of my life.

"What I always say to myself is to enjoy the moment. My present is excellent and I have to continue to enjoy myself. I look at it as projects and the enthusiasm [they bring.]"

Ronaldo helped Juve win Serie A last season, becoming the first player in history to win league titles in England, Spain and in Italy.

"The Juventus project attracted me," Ronaldo said. "It was exciting.

"It was a team that I liked, not only because it's the best team in Italy but it's a combative team that always tried to win the Champions League. I also wanted to win here, like I had done in England and in Spain. I achieved that, something that no player had done."

Ronaldo was recently shortlisted for UEFA Men's Player of the Year award, after also winning the inaugural Nations League with Portugal in the summer.

Tagged under

Karunaratne gives players 'freedom to go and express themselves 100%' - Dickwella

Published in

Cricket

Wednesday, 21 August 2019 04:06

Dimuth Karunaratne, Sri Lanka's relatively new captain, doesn't ride players hard, doesn't tear them down for taking aggressive options, and when criticism is required, he ensures it's constructive. Perhaps this is all a bit sappy, but it is the feedback from several members of this Sri Lanka dressing room.

Thisara Perera spoke of Karunaratne being "like a brother" during the World Cup campaign. Acting coach Rumesh Ratnayake spoke of the calmness Karunaratne spreads through the dressing room. And now, ahead of the second Test against New Zealand, Niroshan Dickwella has given Sri Lanka's fifth Test captain in three years an endorsement of his own.

Dickwella had been Karunaratne's deputy during the Test series victory in South Africa. And although no vice-captain has been officially named for this series, with Dickwella's own place in the XI not assured ahead of the first Test, he spoke about the unique qualities Karunaratne has brought to the role.

ALSO READ: Fernando - Sri Lanka are winning, but it's in spite of the system

"Dimuth is a very different kind of captain," he said. "His way of managing players is different, and every captain has their own style. I've played a lot with Dimuth and what he does is give the player the freedom to go and express themselves 100% in the match.

"What Dimuth says is go and do what you want to do, and what you feel you can do. If we make a mistake, he'll pull us aside and say this happened, why don't we fix that mistake for next time? He talks a lot about being confident about your abilities. And he gives you that confidence."

Sri Lanka have so far won each of the three Tests they have played under Karunaratne, but they arrive now at a venue at which they have struggled. Sri Lanka have lost five of their seven most recent Tests at the P Sara Oval, including their last match to New Zealand here, in 2012. The pitch, Dickwella said, should favour fast bowlers and batsmen more than the Galle surface, on which neither team crossed 300. Sri Lanka's victory in Galle was ultimately comfortable, but the team remains wary of a New Zealand resurgence, particularly at a venue that often provides good bounce for seam bowlers.

"It's a big challenge. Having won one game, we have a big responsibility to win the series. We have the confidence, but we need to keep making good decisions at crunch moments," Dickwella said. "Close-in fielders, including me, have missed some chances in Galle, but those were difficult chances - you don't have even seconds to react. But still, we spoke about that. We're happy to improve on those areas.

"In the batting, we were 142 for 2 and then collapsed to 168 for 7 in the first-innings, so we have to improve on that as well. When it comes to bowling, when one bowler is bowling well, from one end, we need to build a partnership from the other end as well."

Tagged under

How can David Warner emerge from his batting funk?

Published in

Cricket

Wednesday, 21 August 2019 05:05

David Warner shapes to defend Mitchell Starc, misses, and the plastic stumps in the Headingley nets go flying. All manner of dismissals take place in the nets, real or imagined depending on the fields "set" by the bowler or throw-downer, but few quite so dramatic.

The moment rather summed up Warner's Ashes tour thus far, in which he is yet to reach double figures across four knocks. Married up with his closing three innings in South Africa prior to the Newlands scandal ban, Warner is in the second longest streak without a half century of his career - his worst run was eight innings in New Zealand and Sri Lanka in 2016.

At Edgbaston and Lord's, Warner's rapid exits were somewhat less of an issue for Australia, bolstered as they were by the genius of Steven Smith. But with Smith out of action in Leeds due to concussion, the tourists' batting stocks have been made to look exceedingly thin. More than ever, Australia need Warner to find something. The captain Tim Paine is hopeful that Warner will do so this week, referring to Smith's absence as the "poke and prod" the opener needs.

"David, I've spoken a lot about the fact he averages close to 50 in Test cricket and he's done that over a long period of time," Paine said. "I think with Steve missing this game I think it might be the little poke and prod Davey needs. He likes that responsibility and my experience with Davey is when people doubt him and his back is against the wall he comes out swinging. I'm expecting the very best David Warner this week."

How Warner finds his best is somewhat complicated by the way he has approached this tour. For so long a combative, aggressive batsman, his stated goal in England this time around was to calm himself, slow his tempo, and find a balanced rhythm at the crease more sustainable over long innings. During the World Cup, the method worked to a reasonable extent, as he peeled off centuries against Pakistan, Bangladesh and South Africa.

Tim Paine

But in the semi-final against England he was swiftly beaten by a sharply rising delivery from Chris Woakes, and so far during the Ashes has been found wanting in terms of defensive tightness and decisiveness at the hands of Stuart Broad and Jofra Archer, both pursuing a rigorous line at him from around the wicket. It is a method seldom seen against Warner - Broad has admitted he had previously thought primarily about finding Warner's edge rather than constraining him by targeting the stumps - but it is proving fiendishly effective.

One close observer of Warner has been England's captain Joe Root, who has marshalled the plans against the left-hander while also mired in his own poor run of batting form. How does Root think a player struggling for runs can find rhythm and confidence again? It starts with honest self-assessment.

"You need to be realistic about how you are getting out. And be fair," Root said. "Sometimes as hard as it might be you have to give credit to the opposition when they've bowled some good balls. You don't want to be over-critical when you don't need to be. But there are times as well when you got to understand when you got it wrong. And then work it back from there. You don't become a bad player overnight.

"You don't lose the runs you've scored already. And you know you've got it in the bank and you've proven it before. From my point of view, I have got Ashes hundreds in there in the bank and I know and I know what it takes to win games of cricket. Of course from Dave's point of view, we'll be trying to keep him to single figures for as long as possible because he's a proven performer for Australian cricket."

An intriguing returning presence around the Australian side will be Ricky Ponting, who commented during the Lord's Test that Warner need to be showing more positive intent to score. Certainly, this is the view of Warner's longtime batting coach and sounding board Trent Woodhill, who has always focused on the 32-year-old's ability to put bowlers under pressure, leading to fewer deliveries challenging his defence, rather than trying to make him "tighter" or able to bat for longer periods.

Most of Warner's most memorable and impactful innings have been extraordinarily bold in their strokeplay, and it is difficult to see how, given his current struggles in defence, how he will be able to score runs without at least reverting to a more aggressive posture, eyeing off the smallest errors in line or length to pick off. Another window into Warner's state of mind has been the fact that, at slip, he has struggled to hold catches so far - being a primary offender among the five chances put down at Lord's. In a vote of faith, Paine reckoned Warner would be staying in the cordon.

"I think Davey will probably stay in there, and Marnus - for people who haven't seen him - he's probably as good a slipper as there is going around," he said. "And everywhere else in the field, so he'll cover Steve with the fast bowling I think at second slip, and then we have Usman Khawaja who did pretty well in Australia last year for Lyno [Nathan Lyon].

"So we've got a few options there, we've got Matthew Wade who's a wicketkeeper and he can field anywhere. So we've got a number of options to go through that spot if we need to. But I expect Davey to go back there, he's allowed to have a bad day."

That, as much as anything, will be key to Warner finding the runs Australia so dearly need from him at Headingley. Just as he responded to Starc's stump rattler by calmly picking up the broken wicket and resetting for the next ball, Warner needs to put the Edgbaston and Birmingham dismissals out of his mind and strike a blow when battle is rejoined in Leeds. The incentive, to be a key player in the Test match that sees the Ashes retained by Australia, is enormous.

Daniel Brettig is an assistant editor at ESPNcricinfo. @danbrettig

© ESPN Sports Media Ltd.

Tagged under

Fins' Ross leaves NFL's social justice committee

Published in

Breaking News

Wednesday, 21 August 2019 05:59

Miami Dolphins owner Stephen Ross has stepped down from the NFL's social justice committee, the team announced Tuesday.

"Stephen made the decision last week and informed the NFL and members of the working committee that he was going to step aside from the group and continue to focus his efforts on RISE," a Dolphins spokesman said. "He believes in and is still fully committed to the work that has been done by the group and will always be a passionate supporter and tireless advocate for social justice causes, the fight for equal rights and education."

The committee includes players and team owners and is intended to address social justice issues. Last season, members of the committee included Arizona Cardinals owner Michael Bidwill, Atlanta Falcons owner Arthur Blank and Washington Redskins cornerback Josh Norman.

Ross, who was a founding member of the social justice committee, has drawn criticism for hosting a fundraiser for President Donald Trump earlier this month.

Former NFL defensive end Chris Long initially addressed Ross' departure from the group in an interview with Sports Illustrated. He then expanded on the reasoning in a pair of tweets Tuesday evening.

Just read every mention here and they're all pretty shortsighted. We've worked w a number of owners who lean conservative and have even supported trump in the past. However (and I have no idea why I'm explaining this because you'll never concede the point).....

— Chris Long (@JOEL9ONE) August 20, 2019

He held a fundraiser for a guy who called protesting players "sons of bitches" + campaigned for them to lose jobs. The working group is directly involved. You can see how that's a conflict of interest that transcends politics. I respect SR's work w RISE. Don't get it? Can't help.

— Chris Long (@JOEL9ONE) August 20, 2019

Dolphins wide receiver Kenny Stills initially called out Ross in a tweet Aug. 7, saying "Someone has to have enough courage to let [Ross] know he can't play both sides of this." He said last week that he had spoken with Ross and that they have "agreed to disagree."

Following Stills' tweet, Ross issued a statement saying he has been friends with Trump for 40 years and that while they agree on some things, "we strongly disagree on many others" and that he has never been "bashful" about expressing his opinions to the president.

Tagged under

Tat's life: Bird wants tattoos taken off Indy mural

Published in

Basketball

Wednesday, 21 August 2019 05:41

INDIANAPOLIS -- Larry Bird likes the mural, just not the tattoos.

A lawyer for the former NBA star has asked an artist to remove certain tattoos from a large painting of Bird on an Indianapolis multifamily residence. The tattoos include two rabbits mating on his right arm, a cardinal on his cheek and a spiderweb on a shoulder.

Artist Jules Muck painted Bird in a blue basketball uniform. It's a replica of a 1977 Sports Illustrated cover when he played for Indiana State.

Attorney Gary Sallee says Bird "needs to protect" his brand and "doesn't want to be seen as a tattooed guy."

Sallee told the Indianapolis Star that he expects a compromise in which all the tattoos will be removed except one of the word "Indiana" on his left arm.

Muck said she adds things like tattoos to her art to avoid creating a complete copy of a photo and is trying to reach an agreement with Bird's representatives.

"They said the tattoos are the problem," she told the Star. "I can't just do an exact replica of a photograph. Plus, I don't want to. We'll see. It's going to be a matter of how much we have to do to change it."

The Associated Press contributed to this report.

Tagged under

Debating the NBA's most overrated and underrated teams

Published in

Basketball

Wednesday, 21 August 2019 05:50

The 2019-20 NBA summer forecast debuted Wednesday with our experts' predictions for the standings in each conference and records for all 30 teams.

Which teams are most underrated and overrated in the forecast? What were the most surprising results?

After an offseason full of player movement, the Milwaukee Bucks (57 wins) and Philadelphia 76ers (55 wins) led the way in these projections. Get the full projections here, with more picks coming over the course of the next week.

Five of our NBA experts break down the results.

1. What is your biggest takeaway from the results?

Chris Herring, FiveThirtyEight: That the outlook for each conference has seemingly reversed in the past few months. It had felt as if Golden State and Houston were the only two clubs that had a solid chance of reaching the NBA Finals for a while in the West, whereas the East had four or so contenders to reach that stage. Now the East has a pair of teams that look much further along than the others, while the West has at least six teams that can all credibly say they have a decent chance of reaching the Finals.

Jorge Sedano, ESPN: We haven't really seen multiple teams truly be championship worthy out of the East since LeBron, Wade and Bosh had their battles versus Chicago, Boston and Indiana. Since they don't have to go through the gauntlet out West, Milwaukee and Philadelphia clearly qualify as teams that can win the title this season.

Bobby Marks, ESPN: It's interesting how much Milwaukee and Philly have benefited from Kawhi Leonard's move. And on the other side, the West has 14 teams (sorry, Phoenix) that can compete for a playoff spot.

Marc Spears, The Undefeated: Boy, the East isn't respected much -- there are only three East teams in the top 10 here.

Kevin Pelton, ESPN: That people are accounting for the gap between the East and West. I don't think people would say the two best teams in the league are in the East, but the top two projections come from there. That's partially because of the difference between regular-season and playoff performance, but also seems to reflect the way the West will beat up on itself.

2. Which East team is most underrated?

Marks: Brooklyn (45 wins, No. 5 in the East). Yes, Kevin Durant will probably be out, but Brooklyn did add All-Star Kyrie Irving, Taurean Prince, DeAndre Jordan, Garrett Temple and Wilson Chandler to a team that returns many of the same faces from that 42-win team: Spencer Dinwiddie, Caris LeVert, Joe Harris, Rodions Kurucs and Jarrett Allen. Expect Brooklyn to be closer to 50 wins this season and compete for a top-four seed in the East.

Pelton: Chicago (32 wins, No. 11). Statistical projections are largely unanimous that the Bulls should be near .500 this season after adding a number of quality role players (including Otto Porter Jr. at the 2019 trade deadline) to go with the young core that struggled to win games last season.

Sedano: Miami (43 wins, No. 7). You give Erik Spoelstra a top-15 player in Jimmy Butler and the Heat are going to win a lot of games. The last time he had a player of that caliber on a non-LeBron team, Miami won 48 games (2015-16). People don't realize how poorly constructed Miami's roster has been the past two seasons. I'm betting big on Spo.

Spears: After they added Malcolm Brogdon, Jeremy Lamb and T.J. Warren, I'll take the Indiana Pacers (46 wins, No. 4).

Herring: I wasn't in love with some of the Hawks' summer moves (the Jabari Parker signing doesn't strike me as a great fit), but I wouldn't be surprised if they make a slightly bigger jump than what's projected here (34 wins, No. 10). We all know about Trae Young, but if other youngsters like John Collins and Kevin Huerter show linear growth -- and the team can actually learn to make stops -- I think Atlanta could get closer to the high 30s. After a 21-41 start, the Hawks came to life and played nearly .500 basketball in March. They seem another year or two away from doing real damage, but I wouldn't be surprised if they give chase for that last spot in the East.

2:07

The dates to mark off on the Zion debut tour

The hype surrounding Zion Williamson is seldom seen, and Scoop Jackson lists the important dates for when Zion and the Pelicans hit the road.

3. Which West team is most underrated?

Herring: Oklahoma City (33 wins, No. 13 in the West) is the most underrated team by far on this list. I'm not even sure it's debatable whether the Thunder would be a playoff team if they played in the East. (We wrote at FiveThirtyEight that they barely fall outside playoff range in the stronger West.) The real question here is when and whether Sam Presti will find a way to deal off the team's remaining veteran assets, who could surely help other clubs while further enriching OKC's rebuild. If that happens, it's fair to think little of the Thunder's chances. But I feel the current roster -- with a healthy Chris Paul, Steven Adams, Danilo Gallinari and Shai Gilgeous-Alexander -- is pretty decent, and would pretty easily win more games than projected.

Spears: The San Antonio Spurs as a borderline playoff team at 43 wins and No. 8 in the West.

Marks: Sacramento (37 wins, No. 12). The team that won 39 games a season ago is penalized by a deep Western Conference. The Kings bolstered their depth with the free-agent signings of Cory Joseph, Trevor Ariza and Dewayne Dedmon, return their starting five and are still projected to drop two games in the win column for 2019-20. If the Kings can get an All-Star-type season from De'Aaron Fox, the same consistency from Buddy Hield and continued development by Marvin Bagley III, they should win 45-46 games and compete for one of the final playoff spots this season.

Pelton: Dallas (41 wins, No. 9). The Mavericks underperformed their point differential last season, which typically would have translated into 38 wins instead of the 33 games they actually won. If Dallas was starting at 38 wins, the addition of Kristaps Porzingis and improved depth would surely translate into expectations higher than 41 wins.

Sedano: Sacramento. I thought hard about OKC at 33 wins but decided on the Kings. While I don't expect them to make the playoffs, I do believe they'll improve upon last season's win total, even after a big jump last season. Fox is arguably the best young point guard in the NBA, and new coach Luke Walton wants the Kings to play a fast-paced style that fits their personnel perfectly.

4. Which East team is most overrated?

Sedano: Brooklyn. Let me start by saying that I love the Nets' front office and coach. Obviously, the Durant signing was incredible for their franchise. However, he's not playing this season and they're no longer surprising anyone. Irving has an injury history that is concerning and I (like many others) wonder about him being the top option on a team. Also, I don't love the potential fit of DeAndre Jordan playing over Jarrett Allen.

Pelton: Philadelphia (55 wins, No. 2 in the East). I'd be surprised if the Sixers had the second-best record in the NBA given Joel Embiid's limited availability. Yes, Philly added Al Horford and will now have an All-Star center when Embiid sits. But somebody's going to have to play power forward when Horford slides to the 5, and I think those options are a substantial downgrade.

Spears: None of East teams look overrated here.

Herring: It seems ambitious to expect Boston (48 wins, No. 3) to win at basically the same rate as last year. We can certainly debate the switch from Kyrie to Kemba Walker (especially if there was a growing rift between Irving and his teammates last season), but losing Horford's perimeter shooting and defensive versatility, even at his age, will be challenging. The latter is something Enes Kanter will be tested on repeatedly come April. Aside from the new players, though, it's also fair to wonder whether one of last season's issues -- the glut of talented wings who all need shots playing alongside a high-usage point guard -- will be any less a problem this season.

Marks: Washington (28 wins, No. 12). That starts with the Wizards making it well known that the development of Rui Hachimura, Troy Brown Jr. and Thomas Bryant will take precedence this season. Yes, Washington returns All-Star Bradley Beal, but the season-long absence of John Wall, replaced by committee (Ish Smith and Isaiah Thomas), could bring the win total of the Wizards down into the teens.

5. Which West team is most overrated?

Marks: Golden State (49 wins, No. 6 in the West). The Warriors would not be in this category with a healthy Klay Thompson in the lineup to start the season. But 49 wins sounds like a reach for a team that has lost Durant, Andre Iguodala and Shaun Livingston as well as Thompson for at least half the season. I am not convinced the rest of the roster after Stephen Curry, Draymond Green and D'Angelo Russell can play at a playoff level before Thompson returns. The bench is largely made up of unproven players, including Jacob Evans, Jordan Poole, Omari Spellman, Eric Paschall and Alen Smailagic.

Herring: Add me to the list of folks who see a ton of upside for the Mavs going forward. I liked both the Delon Wright and Seth Curry signings quite a bit. But marking Dallas down for more than 40 wins in the stronger of the two conferences strikes me as a small reach, if only because of how long it may take Porzingis to regain a rhythm after sitting out a season to rehab following his ACL tear.

Sedano: I don't think any of the West teams are overrated. Maybe Portland wins fewer than 47 -- I don't love the Hassan Whiteside fit. But Damian Lillard and CJ McCollum are so terrific -- not to mention how good a coach Terry Stotts is -- that I think they can overcome any pitfalls.

Spears: The Houston Rockets at 53 wins, behind just four other teams in the league.

Pelton: Speaking strictly in the context of the regular season, the Clippers (54 wins, No. 2). Statistical projections generally have them in the high 40s or low 50s, which makes sense given a likely load management program for Kawhi Leonard and the possibility that Paul George misses the start of the regular season after shoulder surgery. The Clippers probably won't be at their best until May, which is when they'd want to peak.

Tagged under

NBA preseason predictions: Our experts' picks for 2019-20

Published in

Basketball

Wednesday, 21 August 2019 05:49

The 2019-20 edition of ESPN's NBA summer forecast is here.

Which will be the best and worst teams this season? Which superstar players will win the major awards? What surprises are on the way?

We polled ESPN's panel of basketball experts for their predictions heading into the season. Over the next week, we'll roll out the results right here.

First up: predicted standings and records for all 30 teams, along with the most overrated and underrated teams.

Plus, vote on tomorrow's topic: most likely title teams.

Eastern Conference standings

The Bucks and Sixers are the clear leaders in the East, and they came out with the top projections in either conference.

Will a third team break out as a contender to crash the NBA Finals? And can an up-and-coming team such as the Bulls or Hawks break into the playoff picture?

1. Milwaukee Bucks: 57-25

2. Philadelphia 76ers: 55-27

3. Boston Celtics: 48-34

4. Indiana Pacers: 46-36

5. Brooklyn Nets: 45-37

6. Toronto Raptors: 45-37

7. Miami Heat: 43-39

8. Orlando Magic: 41-41

9. Detroit Pistons: 38-44

10. Atlanta Hawks: 34-48

11. Chicago Bulls: 32-50

12. Washington Wizards: 28-54

13. New York Knicks: 26-56

14. Charlotte Hornets: 23-59

15. Cleveland Cavaliers: 22-60

MORE: 5-on-5: The most overrated and underrated NBA teams

Teams with the same projected record had ties broken before rounding.

Western Conference standings

Continuity wins in the West, as the Nuggets retained their core while adding a nice piece in Jerami Grant, though they held off the Clippers by only a fraction of a win. Then it's a tight playoff race all the way down to Sacramento at No. 12. Even if teams take time working in new additions, the Western Conference will be loaded.

1. Denver Nuggets: 54-28

2. LA Clippers: 54-28

3. Houston Rockets: 53-29

4. Utah Jazz: 52-30

5. Los Angeles Lakers: 51-31

6. Golden State Warriors: 49-33

7. Portland Trail Blazers: 47-35

8. San Antonio Spurs: 43-39

9. Dallas Mavericks: 41-41

10. New Orleans Pelicans: 40-42

11. Minnesota Timberwolves: 38-44

12. Sacramento Kings: 37-45

13. Oklahoma City Thunder: 33-49

14. Phoenix Suns: 28-54

15. Memphis Grizzlies: 27-55

MORE: Projected records, standings for every NBA team

Teams with the same projected record had ties broken before rounding.

Vote now: Who will win the NBA title?

Our experts have made their picks. Now it's your turn to weigh in before tomorrow's reveal: Which team has the best chance to win the 2020 NBA title?

Image credits: David Zalubowski/AP Photo; Andrew D. Bernstein/NBAE via Getty Images; AP Photo/Matt Slocum

Tagged under

His bat handle says what?! 10 of the most hilarious and unforgettable cards

Published in

Baseball

Wednesday, 21 August 2019 05:56

Some players -- like the now-immortal Keith Comstock -- pose for them on purpose. Some are semi-tragic mistakes. Others, well, we just don't know.

What we do know: From bat-handle obscenities to boa constrictors and mascot photo bombs, these are 10 of the funniest and most memorable baseball cards ever.

Billy Ripken 1989 Fleer

With perhaps the most famous error card ever produced, Billy Ripken is known to this day as much for the bat handle pictured in his 1989 Fleer card as he is for his career with the Baltimore Orioles or his famous sibling. The words F--- Face were inscribed on Ripken's bat, a mistake that the former infielder has said stems from that being what he wrote on his practice bats to easily distinguish them from his game bats. Fleer issued corrections of the card without the explicit word, including a highly popular white-out edition.

Cal Ripken 1994 Upper Deck

While his brother Billy's card claim to fame came courtesy of a Magic Marker and a bat handle, Cal's came via the telephone. While the 1990s Zack Morris-era cell phone looks hilarious today, it was the cool new technology of the time -- and Ripken appears to grasp the importance of taking a mobile call from whomever it is he is talking to when his Upper Deck card was snapped.

Mickey Hatcher 1986 Fleer

There was no question that a Mickey Hatcher giant glove card would make this list, with the tougher choice being which Mickey Hatcher giant glove card deserved a spot here. In addition to the 1986 Fleer version pictured, Upper Deck released a 1991 version with Hatcher toting a giant glove over his shoulder.

Jay Johnstone 1984 Fleer

Harry Caray was known for being both a Cub Fan and Bud Man, but it was journeyman backstop Jay Johnstone who had the sense of style to rock a Budweiser umbrella for his 1984 Fleer card. It turns out that the umbrella was actually a form of a hat called a "Brockabrella," with Lou Brock as a spokesman, to keep someone dry while still having their hands free.

Glenn Hubbard 1984 Fleer

Ignore for a moment the giant snake draped over Glenn Hubbard's shoulders in his 1984 Fleer card and you still have a pretty amazing shot featuring a Phillie Phanatic photobomb and some other 1980s mascots appearing in the background. Now, back to that giant snake over Hubbard's shoulders. Yes, that is a boa constrictor -- and a reptile that became part of a card famous enough to have its own bobblehead.

Bip Roberts 1996 Score

The beauty of the Bip Roberts sombrero card comes in the mystery of the Bip Roberts sombrero card. Most players in a card on this list at least give a tell that they know they are in on a joke of some kind, but not Bip. Yes, he is sporting the sombrero -- but that look in his eyes is all serious game day.

Oscar Gamble 1976 Topps traded

A card made to commemorate Oscar Gamble's trade from the Cleveland Indians to the New York Yankees became an iconic symbol of the baseball era that encompassed the outfielder's career. Sporting a large Afro that his hat simply couldn't contain and an elite mustache and announced by the headline "Yankees take Gamble on Oscar" (get it, Gamble ... ), he became a cult baseball hero because of this card alone.

Oscar Azocar 1993 Topps

Oscar Azocar hit only .226 with five home runs over three major league seasons with the Yankees and San Diego Padres, but take one look at this card and there's no doubt that love for his bat was not the reason. In fact, he managed to produce multiple entertaining baseball cards during his short big league career.

Chuck Finley 1994 Upper Deck

During his 17-year major league career, Chuck Finley made five All-Star teams, won 200 games and rocked out guitar-style on a baseball bat at least once.

Rex Hudler 1996 Upper Deck

Rex Hudler is another one of those players with multiple cards that could have earned a spot on this list. But we're giving extra credit for his 1996 Upper Deck issue being one of the rare cards with an entertaining picture on the back -- as evidenced by this shot of him milking a cow in full Angels uniform.

Tagged under

'You're the guy with the ball to the crotch': The inside story behind the funniest baseball card ever made

Published in

Baseball

Wednesday, 21 August 2019 05:55

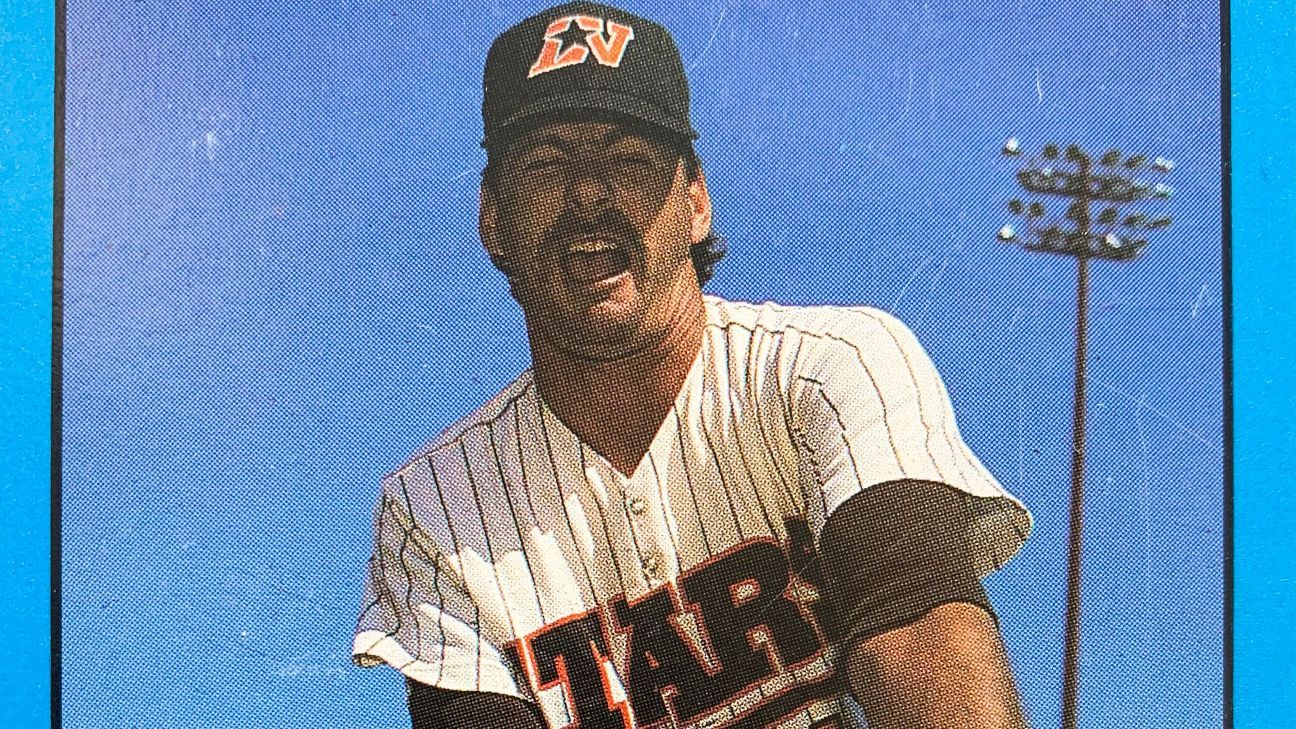

Keith Comstock played on four major league clubs as a journeyman reliever, but his professional career is most often remembered for one thing: a ball to the crotch. Thirty years ago -- in what otherwise would have been a forgotten minor league set -- Comstock appeared on one of the most memorable baseball cards ever made. Here's the story of how it came together, in his words.

When I was a kid, being on a major league baseball card was a top-of-the-checklist kind of thing. It was like a life's dream. You'd keep the superstars, and you'd put the other guys in your bicycle spokes. With the career I had, I was the guy you put in the spokes.

I was drafted in 1976, and it took me eight years to reach the majors. I was traded or released so many times, it was hard to keep count. In 1983, the Oakland A's sold me to the Detroit Tigers for $100 and a bag of balls. I had to deliver the balls. For much of my career, I'd get moved to another team and my wife would pack up the Chevy Vega with our kids and they'd follow me. One time, it took my wife three days to reach my next assignment. On the day she arrived, I found out I'd been demoted.

By the late 1980s, I'd been up and down a few times -- with Minnesota, San Francisco and San Diego. I never had a major league baseball card of myself, until 1988. That's when the Topps card company produced my first real card, like the ones I collected when I was a boy. I'm throwing a pitch in the photo. I was so happy when I saw the card, really humbled. When I got that first card, I didn't keep it. I sent it to my mom. It was like validation for everything that I'd gone through, like here was proof I was a major leaguer. The cool part of that 1988 card is it became a sought-after error card within the Topps set. There was something wrong with the coloring of the "Padres," so I got a little notoriety for that. I couldn't wait to show up in another set.

***

I was demoted again. The same year I got my first Topps card, I was sent to Triple-A Las Vegas, playing for the Stars. I was 32 years old and it was sometime in the late spring when the minor league card photographer showed up. By then, I was just barely hanging onto the game.

I had so many minor league cards of myself that I was getting bored with them. Plus, it was kind of a downer. You didn't want to be in a minor league set. You wanted to have a big league card. And, honestly, another minor league card was a reminder of how my career was going.

There was absolutely zero creativity with minor league cards. You should see my old ones. There was the balance position, where the photographer tells you to raise your leg, like you're ready to throw. There was the one where you extend your throwing hand, like you've just released a pitch. There's the one where you're standing with a ball and glove, doing nothing. Like I said, zero creativity. I'd done so many of those that I was sick of it. So was everyone else.

The photographer who showed up that day was shooting for the 1989 ProCards set, so we were doing this for next year's cards. He had his hat backward, like you might expect from a photographer. While that guy was setting up for the shoot, my teammates started talking about how they wanted to sabotage their own cards.

One by one, they stepped up and posed. Right-handed batters tried to hold the bat like a lefty; left-handed pitchers wore right-handed gloves. They tried everything. The photographer caught every one of them. He had a sheet, or something, that had our numbers and lefty-righty stuff on it. He was really, really strict. He wasn't having any of it.

Finally, it was my turn. The photographer asked me what I wanted to do, expecting I'd do one of the basic poses. I thought about it for a second, and then it came to me: "I want it to look like a comebacker hit me in the nuts," I said. The photographer didn't like that. "Sorry, man," the guy said to me. "I'm under strict rules. I can't take that picture." I pleaded with him, but the photographer wouldn't budge.

***

I was a veteran on the Stars. Because I'd been to the majors, even for a little while, that was a big thing in the clubhouse. Guys looked up to me because I'd made it, even if it was just for a little while. I did what they dreamed of doing, and that earned me respect.

We had a deep team in Vegas, and we ripped through just about everyone in the Pacific Coast League that year. Sandy Alomar was a kid on the team. I think his brother, Roberto Alomar, was there when we did the shoot. There was Jerald Clark, Joey Cora, Bip Roberts and Shane Mack. Bruce Bochy was our backup catcher. My buddy Kevin Towers was there. There was this guy on the team, another pitcher. His name was Todd Simmons. He was the prankster. He heard my rejected plan for my baseball card, but he loved the idea. He knew it had to be done, and he started egging me on.

"Todd told me, 'You're the veteran,' and said I needed to tell the guys in the clubhouse that they shouldn't sign their card contracts unless this photographer allowed me to get a ball to the crotch." Keith Comstock on the conversation that helped make his baseball card a reality

Understand this: When I got my card idea rejected, not everyone had taken their photos. The photographer got all the regular guys done first, and the potential stars would be shot last. No idea who came up with that, but it worked to my advantage. All those guys were still in the clubhouse, 30 minutes from heading to the field.

Todd said I needed to tell the young guys what I wanted to do. You had to sign a contract to do the baseball card, which covered a bunch of stuff and said you agreed that your photo would show up in the set. Todd told me, "You're the veteran," and said I needed to tell the guys in the clubhouse that they shouldn't sign their card contracts unless this photographer allowed me to get a ball to the crotch. So many of those guys were future major leaguers, and it was pretty obvious the card company needed them in the set.

So I did it. I went to the clubhouse, told the guys my idea about the ball and said they shouldn't sign their contracts unless I got this picture taken. They didn't hesitate. It wasn't like some movie moment, though. I didn't mandate anything from them. I wasn't Mel Gibson in "Braveheart." There was no chanting or cheering. Like I said, these guys were 30 minutes from leaving the clubhouse. They were like, "Go ahead." I'm sure they didn't really care.

***

I went to the dugout, got some really sticky baseball tape and tried to stick it to the ball and then to my pants' crotch. The ball was too heavy. It kept falling off. I tried to circle the tape around my quad, but the tape blocked out the ball's seams. I went up and down the dugout, looking for anything that was strong enough to hold a ball.

Then I found the Super Glue. Back in the day, we pitchers used it to cover our blisters. The trainer had the glue in his little kit, so I grabbed it. I didn't want to ruin my game pants, so Todd ran to the clubhouse and got a pair of old ones. I squeezed the Super Glue tube over half the ball. I doused it. I put on the pants, pressed the glued-up ball to them, then tried to let go.

The ball was stuck to my hand. I tried to pull it off, but the ball was about to peel off my pants. I moved my hand and the pants moved. I thought, I am not taking this photo with my hand on my crotch. Someone grabbed a tongue depressor from the trainer's kit and slowly started to pry my fingers off the ball. It took a while, but my hand finally got free. Now I just had to get the photographer.

I walked up with the ball stuck to my pants, and the guy was like, "No-no-no." I was expecting that. I told him that I had a clubhouse full of players who weren't going to sign their card contracts unless I got a ball in the nuts. I looked as serious as possible. The photographer stared at me for a second, trying to figure out if I really meant it. "Son of a bitch," he finally said. "Go ahead."

He gave me one shot. I could feel the ball starting to fall off. "Take the picture! Take the picture!" I yelled. I threw up my hands and closed my eyes. That was it.

***

The guys couldn't believe I pulled it off. I had no idea what the card was going to look like. We won the Pacific Coast League championship that year, then we went into the offseason. I forgot about the card for a bit, but then 1989 rolled around. I couldn't wait to see what the card company did with that photo.

We got the little set of team cards delivered to the clubhouse one day, and we opened them. Sure enough, there I was, taking one to the nuts. The guys thought it was hilarious. I signed the card for any teammate who wanted it. I even signed one for Steve Smith, our manager. That was a great day.

When I finally got a chance to show the card to my wife, I was pretty pleased with myself. I pulled it out. You know what she said? "Why are your eyes closed? That's the best you could do?" She didn't even notice the baseball glued to my crotch. I pointed the ball out to her, thinking it was super funny. She just rolled her eyes. That's all I got, an eye roll.

ProCards must not have been too upset about what I did. Sometime after the set's release, I got an 8-by-10 in the mail from the company. There I am: pinstripe Stars jersey, hat on, eyes closed, mouth open. I framed the photo and for years it hung at my house in Arizona, in a place that I call my Wall of Shame.

I played parts of six seasons in the major leagues, for four teams. I threw my last major league pitch in 1991. I was 35. I got right into coaching, and today I'm the rehab pitching coordinator for the Texas Rangers. I've got three kids and six grandkids. They've all seen that baseball card. Two of my grandsons are 10 and 12. Their mom showed them the card awhile back, and they loved it. Thirty years later and there's Grandpa, getting hit in the nuts.

I love this game, and I have fun with it. It's hard not to when people recognize me from that card. I've had so many conversations with people about it. You're the guy with the ball to the crotch. Fans bring the card to the field and want me to sign it. We have a laugh and then talk baseball. At the end of the day, to a lot of people, this is how I'm remembered as a player. At least I'm remembered.

Tagged under

Katarina Johnson-Thompson set for CityGames double

Published in

Athletics

Wednesday, 21 August 2019 04:56

Heptathlete announced for the long jump and 150m at the street athletics meet in Stockton-on-Tees

Katarina Johnson-Thompson is set to compete at the Great North CityGames in Stockton-on-Tees on September 7 as she continues her preparations for the IAAF World Championships in Doha.

The heptathlete has been announced for both the long jump and 150m at the street athletics meet, which takes place in Tees Valley for the first time after having spent a decade on the NewcastleGateshead Quayside.

“I can’t wait to compete at Great North CityGames next month,” said Johnson-Thompson who impressed at the recent Müller Grand Prix with her best long jump mark since 2015 as she soared out to 6.85m in Birmingham. Four years ago was also the last time the Commonwealth heptathlon champion competed at a CityGames event, when she raced in the 200m hurdles in Manchester.

“I love street athletics meetings and especially when it’s in a location we’ve never been to before.

“Hopefully there’ll be a big crowd there and we can maybe inspire some future Olympians.”

Cllr Bob Cook, leader of Stockton-on-Tees Borough Council, said: “Our High Street will be transformed for the Great North CityGames and I’m delighted Katarina will be joining us for the celebrations.

“This will be an unmissable event, showcasing the best local, national and international athletes and drawing huge crowds to our town centre.”

With a range of events on offer, from 100m sprints to the one-mile distance, and including pole-vault and long jump in a specially-constructed multi sports arena on Stockton-on-Tees High Street, the Great North CityGames kicks off a weekend of first-class sporting action which includes the Simplyhealth Junior and Mini Great North Run, the Simplyhealth Great North 5k, the Simplyhealth Great Tees 10K and finishes with the world-famous Simplyhealth Great North Run on Sunday.

The athletics action starts at 1pm, and is free to spectate with no ticket required. For more information visit greatcitygames.org

Entries are still open for the Simplyhealth Great Tees 10K, which takes place before the Great North CityGames begin on Saturday September 7. To enter, visit greatrun.org/tees10k

Tagged under

Phone: (800) 737. 6040

Phone: (800) 737. 6040 Fax: (800) 825 5558

Fax: (800) 825 5558 Website:

Website:  Email:

Email: