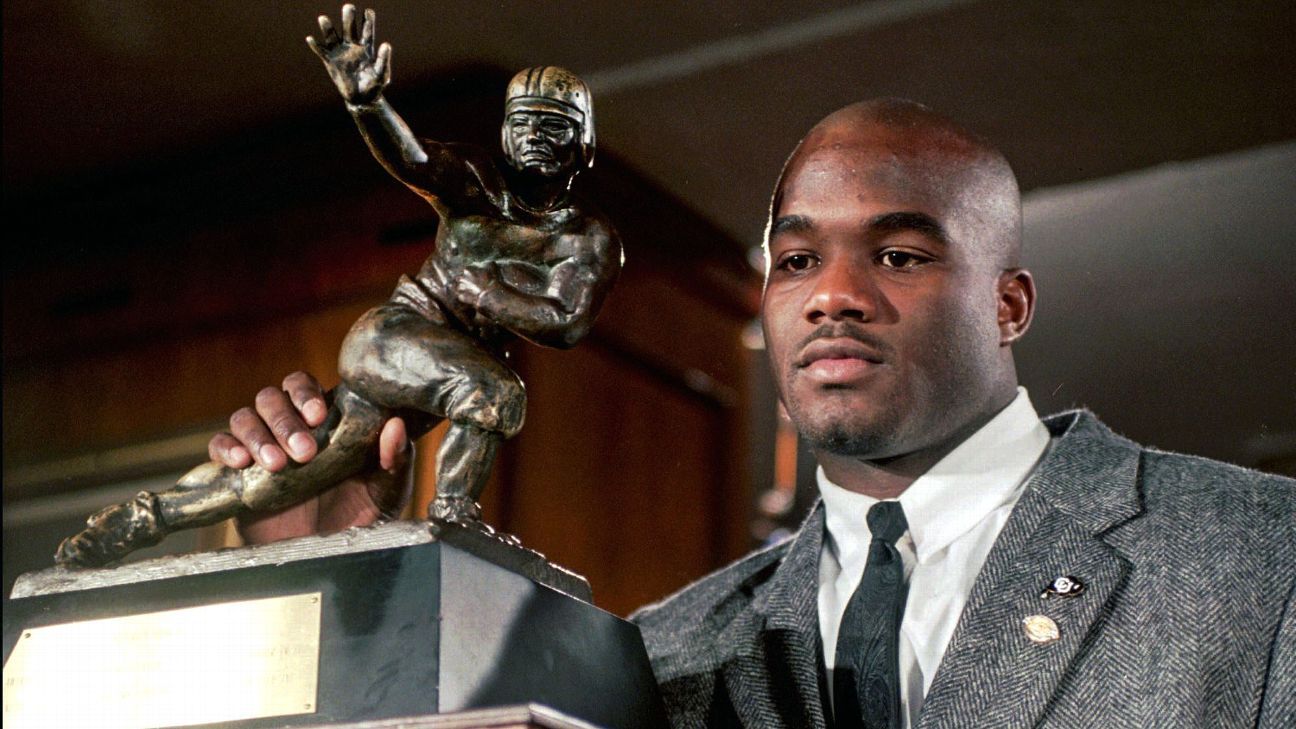

IN AN OLD 45-story redbrick building in lower Manhattan, six college students wait. Kerry Collins, perfectly coiffed and wearing a roomy off-the-rack suit, is nervous. Warren Sapp is working the room, waiting for the after-party. He knows he's not going to win the 1994 Heisman Trophy, but he's on a free trip to New York and plans to live it up. His unlikely sidekick for the weekend is Rashaan Salaam, a running back from Colorado whom he's gotten to know from the college banquet circuit. Salaam is his polar opposite -- quiet and unassuming. He is the baby of the group, 20 years and 2 months old, and has a smile so bright it could melt snow off the Rockies.

Only Salaam isn't smiling as much on this trip.

He does not want to win the Heisman. He doesn't even have a speech prepared. He knows the pressure and attention that comes with the award and wants no part of it. His mother, Khalada, seems equally wary. She has prayed that the Heisman, if he wins it, will not be the pinnacle of his career.

"Dawg, don't even sweat this," Sapp told Salaam earlier in the week. "It's just a trophy."

Sapp knows Salaam is going to win -- he has rushed for 2,055 yards in a single season -- and makes a point to sit next to him at the ceremony so he can say "I told you so."

A man with slicked-back hair and an East Coast accent walks to the dais, turns an envelope sideways and opens it.

"Rashaan Salaam, University of Colorado," he says.

Salaam's teammates back in Boulder leap up and down, hug and light cigars in celebration.

He rises from his seat, then sinks back down for a moment. Everything is about to change.

THE INVITATIONS WERE enough to make a man feel special. For 22 years, they arrived in the fall on fancy paper, then, as technology soared, by email. Who wouldn't want to come back to New York every December for a dizzying week of parties, hospitality suites and a Broadway play?

In 2015, Salaam went to New York with his girlfriend, Shelley Martin. He took her to Benjamin Steakhouse, and they held hands in Times Square. He was happy and uncharacteristically chatty with his fellow Heisman winners, gushing -- as much as Rashaan Salaam could -- about one of his business ventures. He was starting an extraction equipment company in the booming marijuana business in Colorado. He was on the verge of something big.

He might have spent half of his life running from the Heisman, but Salaam occasionally stopped to take in a weekend in New York. He attended the ceremony five times in 22 years.

Perhaps the best thing about Heisman weekend is the camaraderie. It transcends generational gaps. Everyone in the room knows what it's like to be put on a pedestal, to have a lifetime of people stopping and asking them to extend an arm for the pose, even when their arm is just about the only thing still working.

But if you play it right, the Heisman can bring a lifetime of enrichment. It's a name change. In places like Omaha, Nebraska, 68-year-old Johnny Rodgers isn't Johnny Rodgers. He's Johnny "The Jet," Heisman winner.

Knees can crumble, joints can ache, but nothing can take away the Heisman. Only 83 men have won it.

One December, Tim Tebow sought out Salaam and told him how he'd followed him as a kid, and that made Salaam feel good.

BUT MOST YEARS, Salaam seemed out of place.

"He was more of a loner type," Rodgers says. "He talked about how hard of a time he was having. He was not getting embraced and felt like he did not live up to expectations."

Heisman weekend represented another year of having to face the spotlight, of having to answer the what-have-you-been-up-to questions. It meant smiling for photos around people seemingly happier than he was.

In the fall of 2016, Salaam did not return his Heisman ballot. He informed the Heisman Trophy Trust he would not be in New York for the ceremony.

On Dec. 5, 2016, five days before the Heisman presentation, in a park just a mile and a half from the University of Colorado, Salaam fired a bullet into his head. He died carrying $63 and his passport. On the rear floorboard of the black 2006 Suzuki Forenza he was driving was a crumpled-up Post-It note that read, "No funerals wakes memorials let me be in peace!!" A note stuffed in his pocket read: "Some days are good some days are bad. F--- Rashaan Salaam. Don't be sad. No funeral."

After nearly five months of investigating, the Boulder Police Department attempted to sum up Salaam's mindset on the day he took his own life: Friends and family saw instances when he seemed depressed and disappointed with how his life had gone. There were concerns over money, work and his involvement -- or lack thereof -- in the NFL and at the University of Colorado.

Salaam, 42, had a blood alcohol level of 0.25, more than three times the legal limit to drive in Colorado, according to the toxicology report, and 55 nanograms of THC in his blood.

One question that will never be definitively answered is whether chronic traumatic encephalopathy contributed to his death. Multiple people interviewed for this story said Salaam exhibited symptoms of CTE, such as depression, headaches and memory loss.

His mother said the coroner called shortly after Salaam's death and asked whether she wanted to send Salaam's brain to Boston University to test for CTE, but Khalada said no. "I don't regret it," she says. "It's not because we're Muslims. ... I wouldn't have done it as a Christian. No, he -- we -- wanted to bury Rashaan intact."

Salaam was buried on a cold December Friday in the foothills of the Rocky Mountains. Some of the teammates who cheered and smoked cigars in honor of his Heisman were his pallbearers. They carried his light-wood casket through the slushy snow.

Salaam was buried in a white cloth.

"He's not taking anything with him," a Muslim officiant said.

HE WAS GOING to get married. He was going to have two kids and play for the Oakland Raiders for 16 years. Salaam described all of his plans on a high school application when he was 13. He also wrote that he wanted to win the Heisman.

But things were simpler then. All he needed to do was flash his talent, lower his head and run people over and good things would come. His mom pulled him out of the gritty streets of their Skyline neighborhood in southeast San Diego and sent him to Country Day, a private, predominantly white school two buses away in La Jolla. It didn't matter that Country Day played eight-man football. Salaam was so good that the college coaches came.

He had his mind set on attending Cal but had one scheduled recruiting trip left: to Colorado. Salaam was sick of traveling by then and was afraid to fly. He did not want to go to Boulder. But his coach, Rick Woods, personally saw to it that he fulfilled his commitment and drove him to the airport.

Salaam changed his mind by the end of the trip. He called his mom.

"It's beautiful here, Mom," he told her.

Salaam's first two years at Colorado were relatively anonymous. When the 1994 season started, he was neither a preseason Heisman contender nor even the best player on the team. Quarterback Kordell Stewart and wide receiver Michael Westbrook received most of the hype. In the third week of the season, Stewart heaved a 64-yard Hail Mary pass to Westbrook that became the "Miracle in Michigan." Salaam delivered the block that gave Stewart time to make the throw.

"He was always most proud of that play," CU associate athletic director David Plati says.

Salaam, who weighed 224 pounds, could catch a ball out of the backfield, run you over or win a footrace.

The fourth week of the '94 season, the Buffaloes traveled to No. 16 Texas. It was 88 degrees, with humidity so thick that several players needed an IV at halftime. Salaam ran for 317 yards and caught five passes for another 45 in a 34-31 victory. And the Heisman hype began.

Midseason, the Los Angeles Times wrote about Salaam vaulting to the front of the Heisman race and said the attention was so overwhelming that Salaam was disguising his voice when he answered the phone.

"He was a larger-than-life star on campus," says Dylan Tomlinson, who wrote for the Colorado student newspaper in the 1990s. "He would walk around and everyone would run up to him. He was dating the star volleyball player, Rachel Wacholder. He would come to my frat house for parties and would have her with him.

"He'd remember everybody's name and was just a really good guy. So many guys got in trouble, but he wasn't one of them. He loved pot. ... Lots of people do there. You'd be hard-pressed to find anybody who didn't like the guy."

He was happiest around his teammates, particularly his offensive line. Plati says Salaam was "almost bummed" he had to go to New York for the Heisman because it meant he'd miss a big CU recruiting dinner. When he heard about his teammates celebrating his award, Salaam told Plati, "Man, I wish I was there."

The Heisman issues two trophies each year -- one for the winner and one for the school. Salaam did not covet the 45-pound bronze statue. He asked his mom to take his back to San Diego, and Colorado's Heisman rode with Plati and Salaam on a United flight. The trophy sat on a seat in first class with a blue blanket over it.

Every time his teammates or friends tried to congratulate him, Salaam downplayed it. Or worse.

"His exact words to me," says former CU safety Tim James, "were, 'Look, the Heisman was a curse. I don't look at it as a blessing.'"

THE DAY OF the 1995 NFL draft, Salaam had a party at his house in San Diego. He was so excited when the Chicago Bears selected him with the 21st overall pick that he forgot to pack shoes for his introductory news conference.

Jamey Crimmins, who was doing marketing work for Salaam, eyeballed his own size 12 feet and figured his shoes wouldn't be big enough to lend.

"So Rashaan showed up to his professional debut press conference wearing a suit and big white Reeboks," Crimmins says. "That was Rashaan."

When he arrived for training camp -- he was late because of a contract holdout -- he already had a nickname: The Heisman.

Teammates greeted him with sort of a curious reverence that occurs when you're a new Heisman winner.

The coaches worried about their rookie running back because he put so much pressure on himself. "Just relax," offensive coordinator Ron Turner would tell him.

The 1995 Bears were a veteran team with hard-cores who walked around looking angry but loved football. Richard Dent, the MVP of Super Bowl XX, was on that team. So were Mark Carrier and James "Big Cat" Williams.

The defense treated Salaam as one of its own. "He didn't run like one of those cute little running backs," former teammate Jeremy Lincoln says. "He ran like he was a defensive guy."

On Saturdays, Big Cat would cook and would invite some of the younger defensive guys over to watch college football, and Salaam was always part of the group. One of his best friends on the team was Anthony Marshall, an undrafted free safety who, like Salaam, was young and trying to prove himself. They lived near Lake Forest, where the Bears have their headquarters, and sat around at night playing Madden.

Marshall thought it was cool that he was friends with a Heisman winner, and he could never understand why Salaam tried to hide from it. "Dude," Marshall would tell him, "that was an accomplishment."

The Bears' coaching staff was careful with Salaam at the start of the 1995 season, and Turner was doing his part to mentor the young running back. He and his wife, Wendy, would have Salaam over for dinner, and Salaam bonded with their young children. "He loved them," Turner says. "I think he wanted to be one of them."

The plan, at least at the start of the season, was to have the rookie split reps with veteran Robert Green, and Salaam seemed to take comfort in the idea that he wasn't expected to do everything.

Salaam scored his first touchdown in a season-opening win against Minnesota, and by Week 6, he had his first 100-yard rushing game. He finished with 1,076 yards and 10 touchdowns on 296 carries and was named NFC Rookie of the Year.

Turner had big hopes for Salaam. He told him to take a little time off, go see the family in San Diego and then get back to work. No sophomore slumps, Turner told him.

Salaam injured his knee and hamstring in the final preseason game in 1996 and missed the first three games of the season. His confidence wavered. He'd never really faced adversity in football before. He ran for 496 yards that season. He was never the same. In Week 3 of the 1997 season, he broke his left leg and tore ligaments in his ankle. The Bears tried to trade him to Miami in 1998, but when he didn't pass the physical, they cut him.

AFTER NUMEROUS INJURIES and 14 fumbles spread over three years in Chicago, Salaam struggled to find work in the NFL. In the summer of 1999, he tried a comeback with the Raiders. He did an interview with ESPN's Solomon Wilcots and said he had become addicted to marijuana while in Chicago and that it had made him lackadaisical and contributed to his fumbling.

"I wasn't the type of person I was [before]," he said in the interview. "I wasn't outgoing like I was. I was just to myself. All I wanted to do was go home and do what I wanted to do. I wasn't a social person. I was an outcast."

A marijuana addiction was not something NFL decision-makers wanted to deal with in 1999. Salaam didn't make it past training camp, and his comeback attempts in Cleveland and Green Bay failed too.

He joined the Memphis Maniax of the XFL in 2001, reuniting with his old friend Anthony Marshall, who was also trying to hang on.

But Salaam injured his shoulder, and the XFL folded later that year.

He had a stint with the San Francisco 49ers and in the CFL. Neither panned out. He had peaked at 21.

He went to China in 2006 and ran a company called Art of War, which promotes MMA fights. Konrad Pi, a longtime associate, says Salaam was "the ultimate businessman." He says Salaam eventually sold his interest in the company, made money off it and headed back to the U.S.

In 2011, Salaam made headlines when he sold his Heisman ring. A story in Business Insider said Salaam sold the ring to raise money for his MMA venture that "failed to be as fruitful as anticipated."

Friends, mostly old CU teammates, worried that Salaam was in a dark place. He ignored phone calls and would disappear for long stretches of time.

Tim James, who played on Colorado's 1990 national championship team, ran into Salaam at a CU event sometime in the late 2000s. "He was living in San Diego and wasn't really doing much," James says.

One of the few people Salaam called back regularly was Greg Morrissey, an intern with the Bears during Salaam's rookie season. Morrissey helps keep their little network of old Bears players together. He says Salaam never got over the demise of his football career. He lived on an itinerary set by coaches who told him when to eat and sleep and where he was headed. And when everything ended at such a young age, it set his life adrift.

"All of a sudden, they pull that itinerary away," Morrissey says. "You wake up the next day. Well, now what do I do?"

Friends from Colorado encouraged him to move back to Boulder, the last place he really felt as if he belonged. He was in his late 30s. Former CU assistant Jon Embree was the Buffaloes' head coach. A university is supposed to take care of its Heisman winners, Embree thought, especially when it has only one. Embree wanted to create a role in the athletic department for Salaam, maybe as a fundraiser or an ambassador.

"Let's just say it wasn't seen in the same ... I was on a different page than the people involved to make that happen," Embree says. "I don't think they saw it the same way."

Numerous people close to Salaam who were interviewed for this story said that Salaam, who returned to the Boulder area around 2013, was moving back with the hope of working for the university and that when he wasn't hired, he felt isolated.

"I think ... we aren't having this conversation today if he was affiliated with that program in any capacity, be it the mailman or the athletic director," Morrissey says. "There's a reason he moved back from San Diego to Boulder. It wasn't to go skiing. It wasn't to go hiking. It was to be back where he was loved."

David Plati, who accompanied Salaam to New York for the Heisman presentation many years ago and remained friends with him, says Salaam never mentioned a desire to work at Colorado.

"The thing about Rashaan is he would go dark for months at a time," says Plati, the CU associate athletic director. "We couldn't find him a lot of the time. He never, ever mentioned that he wanted a job."

Tim James tried to mentor Salaam. James is a packaging broker and owns a cattle ranch outside of Monterey, California. James implored Salaam to get off his couch and make something happen. He told him to go back and get his degree.

You're not just anybody, he told Salaam. You're a Heisman Trophy winner.

"I told him, 'In terms of life, football is just a snippet,'" James says. "'You've got all this time ahead of you to do good.' He just kind of shook his head. He didn't look at it like that. But his heart was there. He was a good person, and he wanted to help people. And he was real. He was so genuine. But it was hard for him. It was clouded."

SALAAM AND SHELLEY Martin were going to get a dog. A Pomeranian. Salaam would find the friskiest one of the litter, and they'd name her Zee Zee. He would drive through neighborhoods in Colorado looking for the perfect house. He was always talking about the future.

They'd travel together. Salaam loved to drive. He took Martin up to the mountains, with Earth, Wind & Fire on the car stereo, and she was terrified because she's afraid of heights. "He told me he was terrified too," she says. "But all we could do was go up."

Martin has two daughters, and they called him Papa Bear. Around 2014, Salaam started working with the SPIN Foundation (Supporting People in Need). He loved working with children. He arranged to take a group on an Aspen ski trip and called it "Ski for the Heisman." Many of the kids had never set foot on a ski slope.

SPIN founder Robert Hawkins says he texted Salaam on the day of Colorado's homecoming game on Oct. 15, 2016. The Buffaloes were in the middle of a football revival under coach Mike MacIntyre, ripping off six straight wins. Hawkins wanted to know if Salaam was at the game so he could introduce him to a kid.

Salaam did not text back.

HE WAS GOING to open up an establishment called the High-sman Lounge with a friend named John Van Buren. He was going to make it rich in the marijuana business.

Salaam took another career detour when he met a man named Mark Ray at a marijuana function in Denver in the fall of 2013. Ray was recently at the center of a cattle and marijuana Ponzi scheme investigation, and he settled with the Securities and Exchange Commission by consenting to have his assets frozen while not admitting to any wrongdoing. Ray will not talk about the SEC probe. "The only reason I called you back," Ray says, "is that was a good guy. A good guy who had his problems and issues.

"I thought the world of him. I tried getting him to go to have his headaches and stuff checked out, and he'd never do it. He said he couldn't afford it because he had lost all of his money. People took money from him and never paid him back."

Ray says Salaam, unbeknownst to just about everyone, took a job transporting show cattle. He drove through Nebraska and Oklahoma, places he'd gone as a football player, and would be unrecognizable.

According to Ray, a man at a tire station in central Nebraska once asked Salaam if he was a football player. Ray says Salaam replied, "I used to be. I'd rather talk about cattle than football."

Salaam, Ray says, used to stay at Ray's house in Brighton, Colorado. One time, the '94 Colorado-Texas game was being replayed, the one with Salaam's 317 yards, and Salaam left the room. He didn't want to watch it.

"He got up, sat outside on the patio, drank a beer and smoked a joint," Ray says. "I said, 'Don't you want to watch this?' He said, 'Nope. I don't care anything about that s---.'"

But Salaam loved his teammates. He loved catching up with the guys on the old Bears defense.

He talked to Anthony Marshall in 2016. In one of their last conversations, Salaam asked Marshall what he thought about when he looked back on his career. Marshall had no regrets. When he was a rookie, he told him, they gave him $35,000 and a helmet and told him to go make a team, and Marshall got six years out of it.

He reminded Salaam how special he was.

"You're a Heisman Trophy winner," Marshall told Salaam. "They couldn't have given Anthony Marshall a Heisman Trophy."

Marshall has season football tickets to his beloved LSU Tigers, but he does not go to games. He will get in his Winnebago and drive his kids from their home in Alabama to Baton Rouge, park at the stadium and tailgate, then glad-hand and take some pictures on the sideline. Then he retreats to his Winnebago for some peace and quiet while his kids sit in his seats and watch the game.

"Once you get around that field," Marshall says, "you smell the grass and it brings back memories. It bothers me because I know there's no way in hell I can go down there and hit someone without tearing every damn thing in my body."

When he told Salaam about his game-day ritual, Salaam laughed. Marshall didn't have time to dwell on the past. He had teenagers with soccer and volleyball practices. He wonders whether things would be different if Salaam had had that.

"You need something," Marshall says. "Once you leave that game, you've got to have something to be responsible for."

THE MORNING OF Dec. 5, 2016, Salaam called Shelley Martin. "Just know you are beautiful and I love you," he told her.

He received a text that the rent on his condo in nearby Superior, Colorado, was past due. His month-to-month rent was $1,100. Salaam didn't respond.

He went to a 7-Eleven that afternoon and struck up a conversation with a CU student in line. They talked about football and fist-bumped goodbye.

Late in the afternoon, Salaam called Tim James. A year earlier, in October 2015, Salaam had gone out to California and stayed at James' ranch for nine days. He watched the cows and sat by the fireplace and decompressed.

Salaam talked about a cattle drop that nearly went awry. He laughed. The conversation lasted about an hour. He told James he loved the smell of oak burning on the fire. "He was in a good place mentally," James says. "He was checking in."

At 3:42 p.m., less than five hours before he died, he texted James his personal email address. "This still good," he typed. His email name had CU in it.

THE HEISMAN INVITATIONS were sent out this fall. No matter what happens, they will always be sent out in the fall.

"I hope this finds you well," the letter said to its Heisman recipients.

"At the Dinner Gala, we will honor Steve Owens (50th Heisman), remember Rashaan Salaam on his 25th Heisman Anniversary and recognize Mark Ingram (10th Heisman)."

His mother, Khalada, will be at the ceremony Saturday. It will be the first time she's seen a Heisman Trophy in person in at least five years. Her son sold his Heisman in 2014. But the trophy he won for the school is displayed prominently at the CU campus, in Legacy Hall. He is running in a giant photo on the wall next to the trophy, running to a place that very few men get to. He is a Heisman winner. Nothing can take that away.

Kate Fagan and E:60 producer Frank Saraceno contributed to this report.

HOTLINE: If you are in crisis, please take the first step in getting help by calling the National Suicide Prevention Lifeline at 1-800-273-TALK (8255). The call is free, and you will be connected to a skilled, trained counselor at a crisis center in your area.

Phone: (800) 737. 6040

Phone: (800) 737. 6040 Fax: (800) 825 5558

Fax: (800) 825 5558 Website:

Website:  Email:

Email: