MICHAEL JORDAN MISSED. With 35.8 seconds left in Game 1 of the 1997 NBA Finals between the Chicago Bulls and the Utah Jazz, the greatest player in NBA history actually just bricked what should have been the winning free throw. And now, for roughly 26 seconds, the basketball world is in chaos: Jordan is, for the time being, Err Jordan, a lowercase goat, and the voters who had narrowly selected Utah forward Karl Malone over Michael (986-957) for league MVP seem to have gotten it right. Meanwhile, the Jazz are poised to steal Game 1 along with home-court advantage, and Chicago's fifth title and eventual second three-peat are suddenly in jeopardy.

And then, to the rescue steps Scottie Pippen. A future Hall of Famer, at this point Pippen remains something of an introvert, the guy who shrank from this exact kind of late-game spotlight in the 1990 and 1994 playoffs. But with 9.2 seconds left and Malone at the foul line with a chance to seal the win, Pippen conjures and delivers the single greatest line of trash talk in sports history.

It's a line loaded with fascinating cultural, statistical and historical subtext. A line so clever it rescues one legacy, rewrites another and destroys a third. And a line that will ultimately set the table for the 1997-98 Chicago Bulls and "The Last Dance," the documentary that 23 years later will keep us all sane during a sports-less pandemic.

Six magical words, so influential and controversial they inspired their own oral history.

"It's gotta be Karl Malone here. This is MVP time," NBC analyst Bill Walton exclaims after Jordan's miss, as the Jazz set up in their half-court offense with the score tied at 82. But with the shot clock at :02 and the Bulls' defense holding strong, John Stockton forces up a 3 that hits the back of the rim so hard it springs all the way out past the left wing. (Bulls guard Steve Kerr said the rim was loose from the excessive dunks of Chicago's mascot, Benny the Bull.) As Malone hustles laterally to corral the rebound, a trailing Dennis Rodman climbs up his back and is called for a loose-ball foul.

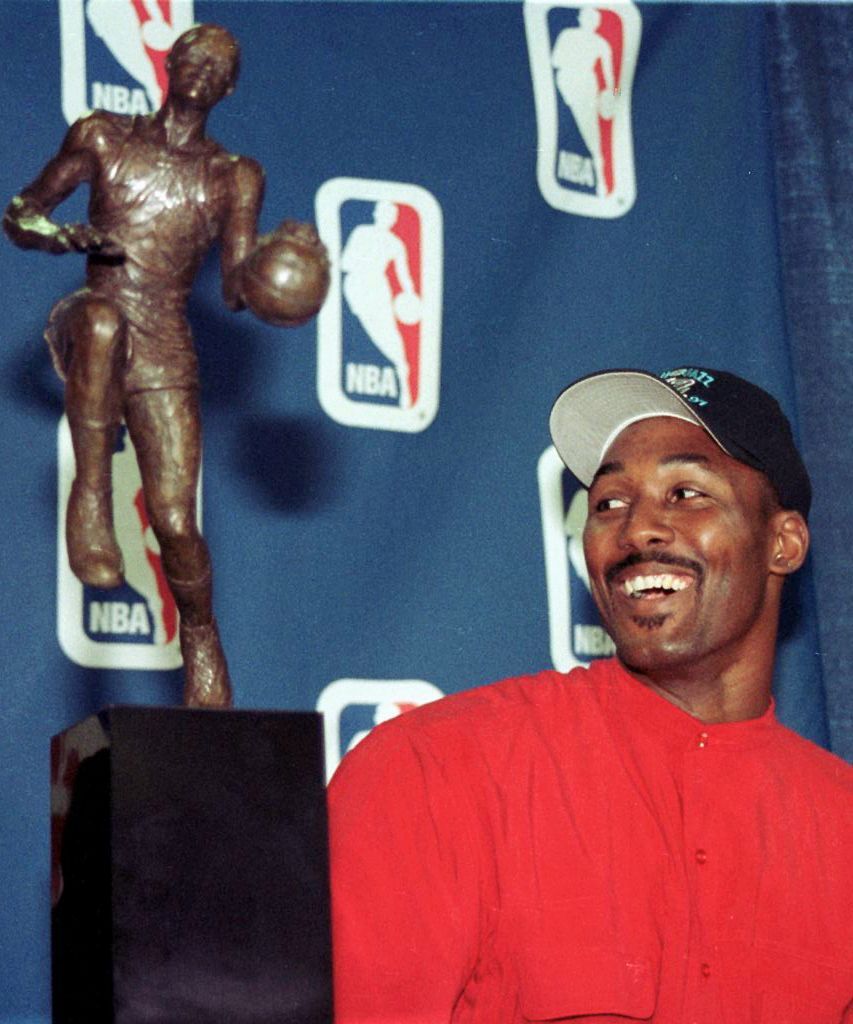

For the first 47 minutes and 50.8 seconds of these Finals, Malone has been on an absolute tear: 23 points, 15 rebounds, 3-of-4 from the line. And with 9.2 seconds left, the newly crowned NBA MVP walks to the line with a chance to rewrite sports history.

Brad Rock, Deseret News columnist, 1994-2019: I used to say that 19,911 people could not make more noise than Jazz fans did, and it was like that in Chicago too. When Karl walked to the line, it was deafening in that stadium. My ears rang for days.

Dave Allred, Utah Jazz vice president of public relations and communications, 1981-2003: We went into this series with the expectation, "I hope we can be competitive. I hope we can take them to seven games." And then you get there and you get in that environment and the intensity is so great and you actually have an opportunity to win the game. I mean, there was a real sense of hope. ... We're sitting there thinking, "OK, when we win, NBC will want this person right after the game and then we have to get Coach [Jerry] Sloan and run back to the locker room." We were already in post-win work mode.

Jason Caffey, Bulls forward: When Karl steps to the line, it was like Tupac's song "All Eyez on Me": You've got the whole world looking at you right there, right then. You're on an island all by yourself.

Rock: It was Karl's game to take. One free throw and maybe NBA history looks a lot different.

With Bulls fans behind the basket already waving wiggly white balloons, Malone begins his trademark pre-free-throw ritual. It's an elaborate sequence that starts with a series of dribbles, twirling the ball up in the air in front of his face, some half squats and a secret whispered, centering mantra -- "This is for Kay and the baby." After struggling mightily from the free throw line early in his NBA career, Malone developed the ritual with the help of a psychological consultant.

Playing in the Jazz's physical half-court style of relentless interior screening and endless pick-and-rolls, Malone relied on this free throw technique a lot. After games, his upper body would often be crisscrossed with deep scratches. (He dished out as much punishment as he endured, though, knocking out David Robinson and splitting open Isiah Thomas' eyebrow.) Malone led the NBA in made free throws eight times, and in 1996-97 he led the NBA in free throws (521) and free throws attempted (690).

But his free throw shooting wasn't always a strength.

Frank Layden, Jazz coach, GM and president, 1979-99: Karl's rookie year, he was so bad they'd foul him on purpose. It was like Hack-a-Shaq. I said, "Look, you can be just another palooka in this league. You're a big, tough guy and you can bang with everybody and you'll play a long time and have a chance to be really good. But if you want to be great, you have to work on your shooting." And he became an excellent foul shooter through hard work.

Sam Smith, Chicago Tribune, author of the bestseller "The Jordan Rules": He was more like Shaq in that sense: In practice he'd make 80%, and then he gets out there and the game stops and everybody's looking at him and he'd tense up. Now, he got to be a much better free throw shooter by working on it, but if there was ever an opportunity to rattle somebody, this was it.

Karen McDermott, author of the study "The Effects of Verbal Insults on Motivation and Performance in a Competitive Setting": The best lines of trash talk are either very brutal, very brazen or very clever. You have this ideal image of yourself, and when that gets undermined by trash talk, you begin to question who you believe you are as a person, what your identity is, and that provokes a very strong reaction of anger and shame. ... If you are susceptible to that kind of suggestion, now it's in the back of your mind. It's like, "OK, now the pressure is really on."

Greg Ostertag, Jazz center: You know what no one ever mentions? Karl still had a big old court burn on his [shooting] hand that he got in the conference finals against Houston, and every time he went to the line in Chicago, he'd look at it.

Mike Shimensky, Jazz trainer, in 1997: It was feeling fine until he went for a dunk [in the third quarter of Game 1]. He re-aggravated it.

Smith: No one on a Jerry Sloan team would ever want to hear that, about some injury as an excuse. The last person who was ever going to make an excuse about an injury was Jerry and Karl.

Layden: We were playing an exhibition game in Mexico once and Karl got his big finger pushed all the way back to his wrist. I mean, it was a mess. They take him to the locker room, and we're all standing around talking to the doctor about flying him back tonight, how this might need surgery, and as we're talking, we hear Karl go "AHHHHH," and he had pulled the finger back into place and told our trainer, "Tape it up." This was an exhibition game, mind you.

Caffey: Karl was another level of strong. We were in Miami once for a game, and I was in a Gold's Gym and they said, "Oh, you just missed the Jazz." Of course I ask, "What was Karl benching?" And they were like he had four plates on either side [405 pounds] and he was throwing it up with ease.

Malone in 1997: When I suit up I'm ready to play and I don't have any excuses at all. You play through a lot of things. Besides, it's the NBA Finals -- what am I supposed to do about it?

Malone's hand was just one of several plotlines leading up to the 1997 NBA Finals that collided in that moment inside the United Center. Standing off to the side, just over Malone's right shoulder, was Jordan. Along with the transcendent MJ, most of the Bulls were household names. Sometimes for the wrong reasons. Up until this moment, Pippen, not Malone, was best known for failing to deliver in two crucial late-game situations during the playoffs. In 1990, Pippen went 1-for-10 in a Game 7 loss to the Pistons while struggling with a migraine, and in 1994 he earned the nickname "Sitting Bull" when he refused to enter the game for the final 1.8 seconds of a game against the Knicks just because the final play had been drawn up for Toni Kukoc and not him.

Meanwhile in 1997, playing in its first Finals, Utah was seen as the scrappy small-market team that always got the calls. The Jazz led the NBA that season in both free throws made (1,858) and free throws allowed (1,796). The Jazz were such a mom-and-pop operation that the person who escorted Jordan to his postgame media session was the 11-year-old daughter of the team's PR director. Malone fit right in. Raised in rural Louisiana, he loved to hunt, fish, drive trucks and, according to Rock, complain about how high his taxes were under President Bill Clinton. Malone might have worked hard to promote a blue-collar image, but the typecasting and stereotyping quickly got out of hand. Jim Rome went so far as to call Malone "the world's only African American redneck." And the Bulls took the ugliness to another level. Coach Phil Jackson referred to Stockton and Malone as dirty players and categorized Mormonism as a "cult." Forward Bison Dele said Salt Lake City smelled like brine shrimp. Dennis Rodman explained his poor play by saying, "It's difficult to get in sync because of all the f---ing Mormons out here."

The contrasts extended onto the court and even into the team hotel.

Ostertag: People hated playing against us because we were going to hit you. We were going to box you out, you were going to get screened. A lot of the credit for that goes to Jerry Sloan. That's the way he played, and that's the way he coached. Jerry was the kind of player who would go in there, get his nose busted, come out, wipe the blood off and go right back in there, and that's how he built his teams too.

Rock: Jerry Sloan's teams didn't do a lot of fraternizing. But I think opponents didn't like Malone because of his elbows, not because he was a country guy.

Smith: It wasn't like Karl was a target of any sort. Scottie was rural Arkansas; they were both Southern kids with the same kind of background, small colleges, hunting and fishing. And that's probably why he did it. If anything, he felt more comfortable and had more of a kinship with Malone than with other players. Maybe Scottie felt he could have some fun with Karl that he might not be able to do with others.

More on "The Last Dance"

Jordan's exclusive interview with Stuart Scott from June 7, 1998

First Take: Which current NBA player displays MJ-like competitiveness?

Rock: The Jazz had John Stockton, who didn't say a word, and the Mailman wasn't really a trash-talker that much, and in the Finals they bump up against a team that had sharpened its trash-talking knives while playing the Detroit Pistons throughout the years. Phil Jackson was pretty good at the psychological stuff, and even if he wasn't, he certainly believed he was. It was all a great bit of gamesmanship on the Bulls' part.

Caffey: Michael was relentless with the trash talk. I mean, he'd talk s--- about everything; he'd talk s--- about your coffee.

Antoine Carr, Jazz forward: The toughest part about playing the Bulls was always trying to figure out how to play them and deal with the referees at the same time. Because you know if you touch Jordan, you're getting a foul.

Ostertag: I saw trash talk affect Karl the other way, usually. Mikki Moore was [with Detroit] in the late '90s. We were playing them once, and he had gone down and scored on, like, two possessions in a row on Karl, and he runs back down the court yelling, "Give me the ball! This motherf---er can't hold me!" And Grant Hill, who was with the Pistons at the time, he runs up to him in the middle of the game and says "Shut. The. F---. Up. You don't say s--- to guys like that." But it was too late. I think Karl had like mid-30s in that game, maybe even 40 points. It still makes me laugh thinking about Grant Hill running up to Moore going, "Duuuuude, no-no-no-no, you idiot, you don't poke the bear."

Caffey: I have a lot of respect for the Mailman. There was just one gator in that pond that was tougher than him, and that was Michael Jordan. ... We got all our swagger from Michael. Scottie was laid-back and straightforward. He took me under his wing. Ron Harper? I hate that guy, he was so insecure. Dennis never said two words. Steve Kerr and Jud Buechler and I, Phil Jackson told us it was our responsibility to go out with Dennis and watch him when he'd go out drinking during the week and make sure he didn't get into too much trouble.

Carr: One thing I did enjoy about playing the Bulls that was different was the city of Chicago was always trying to do something too. You'd be in your hotel room the night before a Finals game in Chicago and all of a sudden a Playboy model would show up at your door with a cake. That happened to me more than once. ... They show up in a trench coat, and when they get to present you with your cake the coat comes off and it's "Welcome to Chicago!" But if you're a young man and all you can think of the night before the Finals is a beautiful girl now, that's going to throw you all the way off. It didn't work on me. It was good cake, though.

Smith: Scottie had so many tribulations in the playoffs. It was a rare opportunity for everybody to write about Scottie and quote Scottie with something humorous and elevated and something other than, "I've got a migraine" or the 1.8 seconds of "I'm not playing because Toni Kukoc got the shot" or how Scottie wasn't a finisher and he never made the last shot. Nationally, that stuff was always hung around Scottie. So for him to provide this final blow to set up Michael, this was almost the perfect example of the way they were the ultimate tag team, the way they fit together: Scottie with the great one-liner and Michael with the last shot.

Smith: It was a poetic ending.

Before taking his spot on the right block for Malone's first free throw, Pippen slid past him at the line, pausing just long enough to deliver the six greatest words in trash-talk history.

Pippen: I just whispered in his ear, "The Mailman doesn't deliver on Sundays."

McDermott: Whenever a line of trash talk makes us confront the reality of who we are and the limitations of our abilities, that tends to provoke anger and shame. To make a free throw requires control and concentration, not brute strength. Anger and shame make it hard to control the fine motor functions you would need in order to perform something like a free throw.

Pippen: It was off the top of my head, freestyle.

McDermott: That makes it all the more impressive. There's no way he would have known to hold it all game and wait until 10 seconds left and Malone's at the free throw line. He would have wanted to get it in before that. So that lends credence to the idea that it really did pop into his head in that moment.

Smith: It's one of the all-time trash-talk lines, and the great irony of it is it's from a guy who didn't trash-talk.

Pippen: It actually wasn't personal. Karl was my guy. He even came to pick me up from the airport sometimes when we were in Utah. My relationship with him is way more than basketball. It was a joke because my brother was a mailman.

McDermott: When you're used to someone talking trash all the time, you can learn to filter it out. But if it comes from an unexpected source, it strikes in your mind even more. So if he had expected it from Jordan or Rodman and that's not where it came from, and it hits you blind side, the lack of expectation makes it more impactful.

Mark Giangreco, WLS-TV Chicago sports anchor: People forgot how funny and clever and smart and cool Scottie was, but when you're always Batman's Robin, it gets lost in the jet stream behind Michael Jordan. He always had it in him. Remember when Scottie dunked on Ewing and then just stood over him and then he got into it with Spike Lee? People always think of Reggie Miller trash-talking with Spike Lee. But trust me, no one ever gave it to Spike Lee like Scottie did.

Pippen: Spike wasn't my hero then. When he came into my house and was talking trash, I just told him: "Take a seat."

McDermott: In this particular case, perhaps accidentally, Scottie Pippen really tapped into that idea of ideal ego and the image that Karl Malone had worked very hard to build of himself -- the Mailman, the guy who always delivers -- and he undermined it.

Smith: You say that line to Michael Jordan, it wouldn't have any effect. It wouldn't have worked on John Stockton either. He would have been oblivious.

Ostertag: It's hard to say if it affected him. You get to the line with the game on the line, there's no telling. He just missed some free throws. Ya know, Steph Curry misses free throws. It happens.

Caffey: Any little word whispered, in negativity or positivity, adds to the tension. I don't care if you're a Zen master, whatever you hear in that moment is still going to come through your brain, somehow, someway.

Malone's routine goes off without a hitch. Dribble. Twirl. Catch. Twirl. Catch. Bounce. "This is for Kay and the baby." So far in the 1997 playoffs, Malone has made 78% of his free throws. And for his career, he turns out to be a 77% free throw shooter on Sundays -- highest of any day of the week. But after digesting Pippen's line, all the kinetic smoothness seems to drain from Malone's motion. With a locked elbow, he jerks the ball off his fingertips and it clanks badly off the back right side of the rim, bouncing halfway down the left baseline.

Pippen immediately steps in front of Malone in the paint, apparently to remind him of what just happened. The Mailman scoffs back, "Yeah, yeah," before walking away, hands on hips, toward half court to compose himself.

McDermott: Once Malone missed the first one, it was almost inevitable that he was going to miss that second one. Because now the idea Pippen planted had really taken hold.

Smith: If there is a ranking of such things, and I have no doubt that probably somebody has created such a list -- then this line would definitely have to be on there. The perfect thing about it was the cleverness: It's Sunday, it's the Mailman. It just fit. It was like a great lede to a news story: the perfect tone at the perfect time, which you just don't hit very often.

Pippen: That was a big game. We needed that game. [I didn't know I had gotten to him] until after he bricked them.

Dribble. Twirl. Catch. Twirl. Catch. Bounce. Whisper. Once the second shot is in the air, Malone is so certain it's going in he begins to backpedal to set up on defense. The ball skims the front of the rim, however, and goes halfway into the cylinder before ricocheting out and into the hands of Jordan, who has inexplicably outmaneuvered 6-9 Carr for the rebound. Malone can't believe it. He turns away, closes his eyes and drops his chin to his chest. During the Bulls' ensuing timeout, Malone can be seen cursing himself out.

The shame and anger McDermott says he's likely experiencing are well-earned: In the past 40 years, Malone is one of only three players to miss multiple free throws with a chance to take the lead in the final minute of a Finals game.

Malone in 1997: I'm from Summerfield, Louisiana, and we don't have any excuses. I don't have any excuses, and I'm not going to use any. I didn't make the free throws. They felt good. I just didn't make them. They were big free throws, but it shouldn't have come down to that.

Caffey: Those two shots could have possibly determined that whole series for Utah, so Karl will never live that down. He's gonna have it in his head for the rest of his life.

Allred: Maybe it's my fault. Just as Karl's about to shoot, I turn to Kim Turner, one of our other PR guys, and I say, "We are going to win this game!" You just instantly go from total euphoria to, "Oh my gosh, no," and just when it can't get any worse, you see Jordan with the ball.

Pippen inbounds the ball above the arc to Kukoc and sets a screen for Jordan coming up from the left block. At the top of the key with 1.7 seconds left, Utah's Bryon Russell swats at the ball with his right hand, leaving him off balance, now totally at Jordan's mercy. Jordan glides left to the top of the Bulls logo and elevates from 21 feet. The shot is so pure the net barely shivers. Jordan assumes his classic game-winner pose -- upper lip tucked in, right fist punching air -- when Pippen, the one who made it all possible, arrives and wraps him in his arms.

Jordan in 1997: Down the stretch, it was nip and tuck, and it could have gone either way. You know, I missed a free throw. Karl comes down and misses two free throws. So, I mean, the MVPs didn't do too much down the stretch until I was able to knock the shot in. It was going back and forth, and whoever made the best plays down the stretch was going to win the game.

Ostertag: Apparently it got in Karl's head. Karl would say it didn't, that he just missed the shot, and that might be true. That's part of being one of the greatest of all time. Kobe, Shaq, LeBron, Jordan -- in our sport, you can't play in the past. Pippen says what he says. You missed those free throws. OK. Those free throws are not the reason we lost that game. You gotta get back, play defense and try to stop them from scoring on the next possession. We didn't.

Giangreco: Malone was pissed. Somebody repeated the line to him after the game and asked about it, and he was real short with them. The frustration level was so high.

Smith: He was defensive and down and tried to brush it off, but you could tell he was embarrassed by it as well.

Malone in 1997: That didn't bother me. Scottie and I are competitors, and I consider him a friend. I can say that because I don't have a lot of friends in the league.

Pippen: I hate that that quote ever got out because no one really got it. It was more of a joke between us.

Giangreco: We couldn't hear what he was saying on the court during the game. In the press conference, somebody asks, "What'd you say there?" And this s--t-eating grin crosses his face. He had it loaded in the chamber and you could tell he just couldn't wait to repeat it. He was so excited. So with that big, deep, huge baritone he goes, "I just said, 'The Mailman doesn't deliver on Sundays,'" and he starts laughing himself, and the whole room just cracked up. Everybody just went nuts. And Scottie enjoyed every second of that.

Smith: Everyone in the press room was fighting over that line. I'm going to use it in my story. No, I'm using it in my column. Especially because it was Pippen. Scottie wasn't exactly the lighthearted kind of guy. He was not somebody who was quick with a quip, really ever. ... This was something Jordan would have said. It would have been the ideal Jordan one-off trash-talk line, so much so that we always wondered if Jordan had fed it to him. Nobody ever copped to that.

Rock: I wrote something along the lines of, "Of course it would be Jordan, how else would you expect it to play out?" It bothered Malone. I don't know if he was scared. The head game was hard on him. It's a fascinating case study. It affected him in that moment and he missed those two free throws and that game really set the tone for the whole series.

Smith: Jordan laughed about the line afterward, I'm pretty sure. He was asked about it, and he commended Scottie. I think Jordan did acknowledge that, yeah, Scottie had bailed him out, that Scottie had saved him as well with that Mailman line. And the Bulls never trailed in a series during their second three-peat.

Caffey: That line became like a joke in the locker room. Everyone was going around saying it. It was the talk of the team. Like when a rapper comes out with a great line and everyone's repeating that line. That's how we were as a team, singing that line out loud, The Mailman Doesn't Deliver on Sundays.

Carr: I don't think it had anything to do with Pippen. I just think the Bulls were lucky. They got the proper calls at the proper time or else it would have been the Utah Jazz with the championship. One or two calls in this thing, it changes the whole complexion and then it's a documentary on the Jazz's first championship. So we continue with the story on the great Michael Jordan.

Allred: I'm still emotional about how close we were to winning that game and stealing a game that no one would have ever expected us to win. But we felt that over and over and over in those Finals games the next two years. That kind of set the standard for what those next two years of the Finals were going to be like.

McDermott: If you're looking at just one-off lines, this is certainly up there. Because it was so clever and so pivotal in terms of outcome.

Pippen: To this day, I think that's the greatest line in basketball.

Three days later, a still-rattled Malone shot 6-of-20 and finished with 20 points in a 97-85 loss in Game 2. Afterward, Jazz coach Sloan said, "I thought we were intimidated right from the beginning of the game."

But after returning to Salt Lake City, Malone responded, scoring 37 in a Game 3 win. When asked why Rodman struggled to guard the Mailman, Jordan replied, "He's going against one of the 50 greatest players in the game -- Karl Malone is not lunch meat." In Game 4, on Sunday, June 8, Malone found himself in a familiar position: at the free throw line with Utah up by 1 and 18 seconds to play. This time, when Pippen tried to deliver the line again, Malone and the Jazz were ready. Utah guard Jeff Hornacek blocked Pippen's path to Malone, who sank both free throws. (With the line no longer effective, in the 1998 Finals, Harper resorted to yelling "Rogaine!" at Malone while he shot free throws, a reference to the hair-growth commercials that featured the Jazz forward.)

Malone in 1997: I knew what he was doing, trying to talk to me. He still talked to me the whole time I was shooting.

Hornacek in 1997: Karl said Scottie got to him earlier and said something about the Mailman not delivering on Sundays. And Karl said something back like, "Yeah, but Federal Express will." Scottie was inching his way over toward Karl, and I thought he was going to say some more stuff, and I just wanted to get in between them and not let him get any more words in there.

Malone in 1997: In life, sometimes you never get a second opportunity. As a player, you wish sometimes you'd get another opportunity. And I did.

Pippen in 1997: I guess he delivers on Sundays here.

The Mailman's delivery remained erratic, at best, in the Finals. The Jazz lost Games 5 and 6 and the Bulls were now two-thirds of the way to their second three-peat. All told, Utah dropped three games in the 1997 Finals by a combined eight points, and in those tight games, after Pippen had dropped his iconic line, Malone shot 12-of-26 on free throws. His performance in the Finals made everyone, including Malone himself, question whether the MVP voters had made a mistake.

Malone in 1997: [The greatest player in the game] is Michael Jordan, like everyone thinks. Down the stretch, Michael wanted the ball in crunch time, got it, made the shot. It's hard to argue about that.

Smith: This ended up being the series with the Jordan "flu game," with a sick Jordan collapsing into Pippen's arms. And once that happened, it overshadowed everything. By then, no one even remembers what happened in Game 1 or what Pippen said to Malone. That flu game defined the series, and every other thing that happened got washed away in that flood.

Malone would end his 19-year career with the most points (36,928, second all time), the most rebounds (14,968, then seventh all time) and the most playoff appearances (19) in NBA history among players to never win a championship. He reached the Finals for a third and last time with the 2003-04 Lakers.

Rock: In 1996, the Jazz lost a Game 7 in Seattle and missed their first chance to get to the Finals. Afterward there were two buses on the tarmac at the airport. I look over at the team bus and players are passing out sack lunches, and I see Karl and he's relaxed and laughing. No one was more of a warrior during games, but when it was over, Malone could move on. I don't think he took it lightly; it was just, once the pressure was off and the game was over, Karl was ready to go hunting. He looked OK. Then the door to the team bus opens and Stockton gets off and he's got this nine-mile stare, staring out across the tarmac and into the Pacific Northwest. He's standing there, and he can't live with the loss. It's eating him alive. Thirty seconds later, the bus door opens again and here comes Jerry. And I still have that mental image in my head of those two standing there, hands in pockets, staring out into the distance, and back on the bus is the Mailman and he's moved on.

Malone in 2004: [In Utah] I started saying, "Oh, I've got to pick it up," instead of just playing relaxed. It was unbelievable, not only because I was being paid the most money in the state at the time but with that comes expectations, and I tried to approach it the same way with the Jazz. I never really got to enjoy it.

Rock: The last I had heard, both he and Stockton were still using flip phones. Talk about old-school. A few years ago, I tried to text him because he never answers his phone. So I text a few times and finally a text came back: "Is this Brad?" I said, "Yes, I wanted to talk to you about such and such." And after a few minutes he texted back: "GET REAL." And I haven't heard from him since. So my guess is he won't watch the documentary at all.

Layden: We never talked about the Finals. He wasn't an "Alibi Ike." He never made excuses. If you lost, you lost. That's all. Walk out and get after it tomorrow.

Rock: Jordan and the Bulls overshadowed everything. But over time, as you look back at it, a lot of people go, "Hey, wait a second, the Jazz were one free throw by the MVP from this whole thing being a completely different story." Things were close enough in that series to still think even to this day: What if Malone makes those free throws? What if the Jazz win Game 1 in Chicago? A couple things change, starting with those free throws, and history is completely different.

Pippen: To this day, Karl is one of my closest friends. He has never said anything to me about the line.

Phone: (800) 737. 6040

Phone: (800) 737. 6040 Fax: (800) 825 5558

Fax: (800) 825 5558 Website:

Website:  Email:

Email: