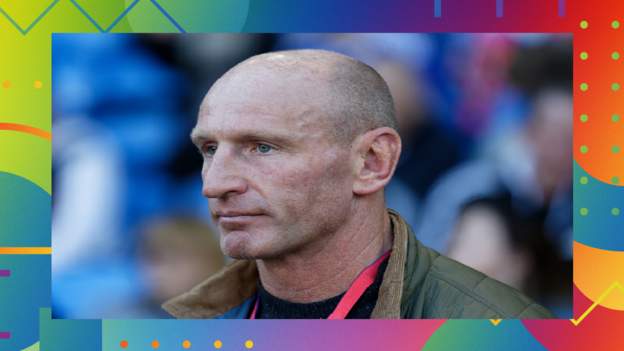

Gareth Thomas looked straight down the lens of the camera, his voice wavering slightly.

The former Wales rugby union captain announced he was living with HIV - and was committing himself to addressing the stigma that existed around the subject.

Just after 10pm on 14 September 2019, the video went live on Thomas's Twitter page.

The whole clip lasted less than 90 seconds, but sent ripples around the sporting world. Messages of support poured in, as the video racked up nearly five million views.

For LGBT+ History Month, Thomas spoke to BBC Sport about life since his announcement, and how he's using his platform to help dispel some of the myths that still surround HIV.

'I knew nothing about HIV'

For Thomas, being strong has always been important.

"It was, and still is, a big representation of what I am," he says. "Physically, I like to stay in shape - because it also helps me to believe I can overcome certain things."

That strength served him well during a glittering dual-code rugby career.

He started in rugby union, winning 100 caps for Wales and captaining the British and Irish Lions during their 2005 tour to New Zealand, before switching to rugby league and leading his country to a dramatic victory over France in the European Cup.

In 2009, Thomas showed strength of a different kind by revealing he was gay at a time when few male sports stars spoke about their sexuality.

But none of that prepared Thomas for the day he was diagnosed with HIV.

"It was one of the most petrifying experiences of my life," Thomas remembers.

"I knew nothing about HIV - and the reality is there's a version of self-stigma as well, where the person themselves doesn't understand the subject.

"I thought all the strength would drain away from me slowly, without me being able to control it or get it back.

"I thought I was going to live a very lonely life after that, a very sad existence, where I would just gradually get weaker and weaker, paler and paler, until I died."

'Living with HIV in 2021 is not like it was in the 1980s'

Thomas's views had been heavily influenced by the legacy of media coverage from the 1980s and early 1990s, where many of those with HIV were eventually diagnosed with Aids.

"As a society, we feel as if we 'know' what HIV is," he says.

"So to try to say to me or other people, 'forget what you thought it was, this is what it is', is a very difficult proposition. I still thought I was going to die."

But the development of new treatments, including anti-retroviral drugs, mean relatively few people in the UK now develop serious HIV-related illnesses.

The same treatments can also reduce the level of HIV in someone's blood to undetectable levels - and if the levels stay undetectable for six months or more, it's not possible to pass the virus on.

"Living with HIV in 2021 is not like it was in the 1980s," Thomas says.

"I take one tablet a day, and am undetectable - which means you can't trace the virus in my blood.

"That means through no activities, whether sporting or otherwise, would I put anyone at harm of contracting HIV through me."

So why hasn't the public perception of what it's like to live with HIV evolved as quickly as its medical treatments?

Thomas says he doesn't have an answer.

"For any other illness, if medicine had moved so far, it'd be celebrated," he says.

"It'd be something people would want to know about. But now, it's only when people get a diagnosis - or a friend or a relative tells them that they're living with HIV - that they start to unravel what it's like."

'You can educate people in front of your eyes'

True to his word on that original video, Thomas is working hard to dispel the stigma that still exists around living with the virus.

His 'Tackle HIV' campaign has attracted the support of former players such as Matt Dawson, while the success of Channel 4 drama It's A Sin, broadcast in January and February, means more of us are having open conversations about the subject.

But there's still work to be done.

Research by 'Tackle HIV' last year indicated more than a third of people wouldn't play a contact sport against an opponent they knew had HIV - while Thomas himself concedes that, if he'd been diagnosed with the virus during his playing days, he wouldn't have felt comfortable telling his team-mates.

"I wouldn't want to create a situation on the field where people would judge me for my HIV status rather than anything else," he says, "or an environment where I could give fans ammunition by making the one thing I loved every week a terrible experience by being able to discriminate against me from the stands."

Even so, Thomas firmly believes using his platform to start conversations about HIV is an important way to help normalise the public's view about what it's like to live with the virus.

"It's difficult to give a generic message, as this is a topic that's very personal," he says.

"But I believe the conversation around living with HIV - and the education that surrounds it - has to be had.

"And if you feel like you have the strength to ignite conversations and find really good allies, you can educate people in front of your eyes - and that's really important."

Phone: (800) 737. 6040

Phone: (800) 737. 6040 Fax: (800) 825 5558

Fax: (800) 825 5558 Website:

Website:  Email:

Email: